Pharmaceutical Compliance Congress 2025

March 24th, 2025

View

Consero’s Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer Forum

March 6th, 2025

View

TDI Promotes Eliza Ehrlich to Partner

January 29th, 2025

View

Due Diligence & Strategic Advisory for Australian Energy

December 2nd, 2024

View

Pre-acquisition Due Diligence on Mining Asset in Western Australia

November 7th, 2024

View

TDI Appoints Jay Truesdale as New CEO

October 31st, 2024

View

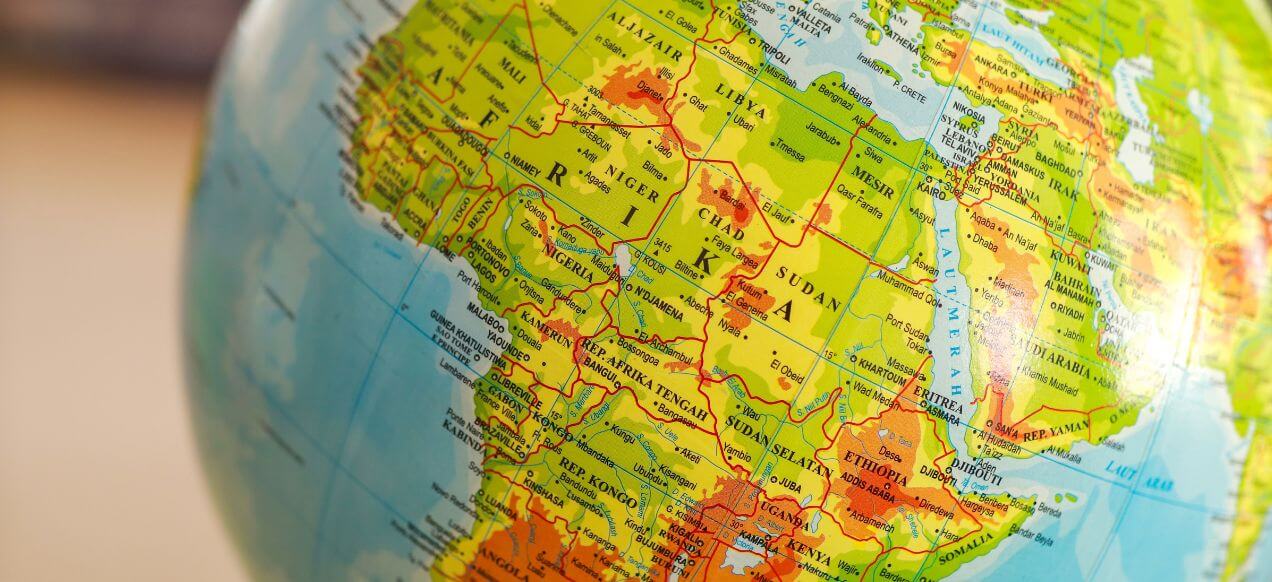

Investigative Due Diligence and Risk Intelligence in Egypt

September 19th, 2024

View

Market Entry And Geopolitical Assessments In Africa

August 5th, 2024

View

Marc Eigner Joins TDI as Board Member

July 2nd, 2024

View

Managing Compliance Risks In Europe And The Americas

June 12th, 2024

View

Due Diligence In South Asia

May 21st, 2024

ViewSign Up for Regular Updates on Industry Trends and New Research:

By signing up for our newsletter, you are consenting to receive periodic news from TDI. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link at the bottom of our emails.

Trusted advice for your most complex problems

TDI combines deep expertise and industry-leading software to help clients successfully manage risk. Contact us to find out more.